© 2016-

Need any help? Contact Us

ՀՐԱՏԱՐԱԿՎԵԼ Է «ՀԱՅԿԱԿԱՆ ՈՐՄՆԱՆԿԱՐՉՈՒԹՅՈՒՆ» ԺՈՂՈՎԱԾՈՒՆ

Karen Matevosyan

Doctor of Historical Sciences

DADIVANK AND ITS FRESCOES

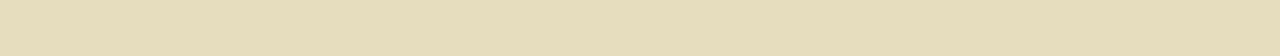

Dadivank is one of most ancient monasteries of Verin Khachen province of historical Artsakh region in Armenia, located on the left bank of Trtu (Tartar) river (the right tributary to Kura), in a wooded picturesque place. The monastery also has a second name, Khutavank.

According to the tradition, the sanctuary was founded in the place of martyrdom of one of the seventy of Christ’s disciples, Dad or Dade (Tadeus), in the 1st century, which later turned into a monastery. Dadivank has flourished especially in the 13th-

Dadivank, which was abandoned in Soviet times, was part of Azerbaijan. In 1993 the area was liberated, and since that year the monastery is in the part of the Nagorno Karabakh Republic, belonging to the Artsakh Diocese of the Armenian Apostolic Church. In this new period (especially in 1997-

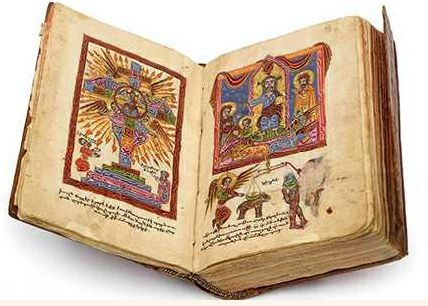

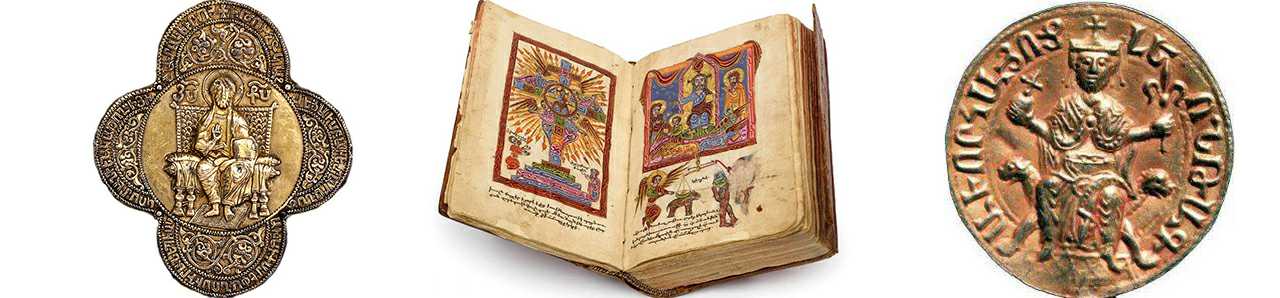

One of the merits of Dadivank is the frescoes preserved on the northern and southern walls of the Cathedral, which have not been studied as necessary due to the fact that they were previously faded and covered with smoked layers. For many, it was not even clear what types of imagery are there. In 2014-

Dadivank’s frescoes, which are the best preserved ones in the Artsakh region, are remarkable in the subject matter. One of the images on the southern wall represents one of the greatest Christian saints -

During the cleaning and restoration of the fresco, a very important discovery was also the inscription on a painting, in which the exact date of the frescoes was mentioned: 1297.

Current study concerned to the frescos of Dadivank Monastery, but first we briefly get acquainted with the certain episodes of the monastery’s history and the historical information related to the circumstances of creating of frescos.

FROM THE HISTORY OF DADIVANK

There are enough publications on the history of Dadivank, churches and other architectural structures, sculpture, epigraphies, center of writings and the restoration of monastic complexes.

In the literature on the monastery, the researchers while speaking about the foundation and the origin of its name usually first quote from Chronology of Michael the Syrian (12th century Assyrian bishop of Antioch). It says that by the order of the apostle Thaddeus, one of the seventy disciples of Christ, Dad (or Thaddeus) went to the northern part of Armenia, in particular, the Little Syunik (Artsakh) region, where he martyred and on the place of his martyrdom a monastery was founded in his name. However, the researchers did not address the fact that this testimony was found only in the Armenian translation of the Michael the Syrian’с Chronology, whereas Syriac original does not have such evidence. Consequently, it should be assumed that in the Chronology this information was included by its Armenian translator -

It is very important that this bibliographic information on the founding of the monastery is confirmed by the lithographic testimony recorded in Dadivank itself. Particularly in the inscription of 1224 on the west wall of Cathedral Church, Grigor, son of Hasan states that he made a donation to the “Dad’s Grave”. In other words, there was no doubt that the monastery was in the place of the martyrdom of one of the 70 disciples of Christ, the place where the tomb was. This should be added to the results of the excavations of 2008, according to which supposedly opened the Dadi’s mausoleum: in the future a big single-

Dadivank was also mentioned in the “History” of historiographer Movses Kaghankatvatsi. Talking about a case in the 9th century, the historiographer writes that Varaz-

We do not address the testimony of a later period about the naming of monastery after Dad. As about the second name of the monastery, though it is often mentioned in the literature that the place was called Khutavank because it was built on khut (hill) near the river, more probably this name comes from the name of a rather large village of Kuth, which at that time was close to the monastery and belonged to it. It is a good idea to mention that the name is more common in late-

The main sources of the history of Dadivank are the local wall inscriptions from 12th-

THE BUILDINGS OF DADIVANK

Most of Dadivank’s buildings were built from the late 12th to the beginning of the 14th century. At that time, the monastery was located in the domain of the princes of Haterk, which originated from the ancient royal family of Artsakh, Aranshahiks. From the 1320s, the Dopians, a noble family originated from the sister of Zakare and Ivane Zakaryans, Dop and the prince of Artsakh, Hasan, became patrons of the monastery. One of the sons of this couple, Hovhannes, who was the leader of Sanahin, then -

The architecture of Dadivank is properly presented in professional literature. The phase of construction of the monastery throughout the centuries through the plans has been thoroughly represented by Samvel Ayvazyan in his book.

On the northern side of the fronted part of the monastic complex are churches, the courtyard, the chapel, and in the south -

A small domed church with a brick-

In the southern part of the monastery complex is the other group of monastery buildings. Here the most eminent structure is the zhamatun with four pillars built in 1211. To the west of it there is a dining-

The main monastery, St. Cathedral Church, as it was mentioned above, was built by Hittzard princess Arzu Khatun, in memory of her late husband, Vakhtang and her two sons, the eldest was martyred in the war against the Turks. This testifies the extensive building inscription on the southern wall of the church (1214), which also mentions numerous donations to the monastery.

The head of the monastery, St. Cathedral Church, as it was mentioned above, built the Haterk princess Arzu Khatun, in memory of her late husband, Vakhtang and her two sons, the eldest of whom were martyred in the war against the Turks. This is evidenced by the 1214th wall of the church wall an extensive construction protocol, which also mentions numerous donations to the monastery.

The name of the church, starting with the building inscription, until numerous donation protocols on its walls, is mentioned as “Katoghike” – Cathedral Church. This church, which is the only building with monumental stone, is a rectangular, cross-

THE DECORATION OF ST. CATHEDRAL CHURCH

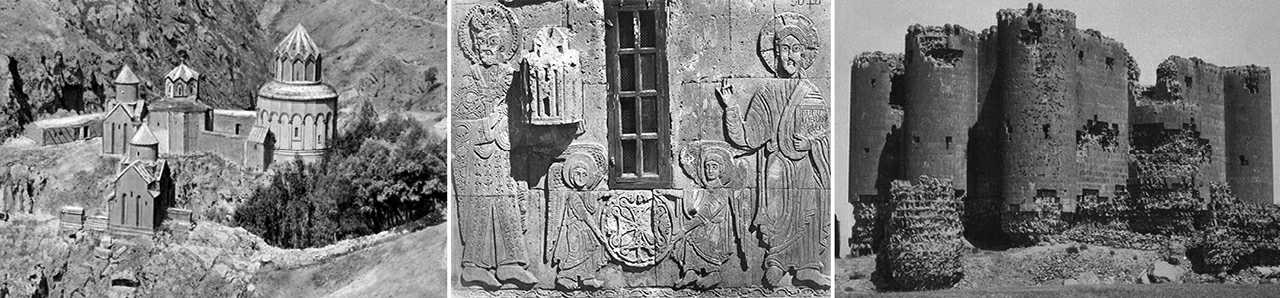

The Cathedral Church, founded by Arzu Khatoun, has the most luxurious decoration among Dadivank’s buildings, both inside and outside. On the outside, the western (main) and northern (now closed) entrances and the trimmings are the main parts with sculptures, as well as the bas-

The eastern wall has a similar composition, but both characters now have been preserved in the size of the bust. On the left there is a bareheaded person with stressed halo, and on the right is a mature man with a noble cap, a small halo and a thick beard. The researchers are rightly asserted that a man with noble outfit is the dead husband of Arzu Khatun, Vakhtang, and the saint in front of him is St. Dad, whose name bears the monastery.

It is possible to have some idea about the internal decoration of the Cathedral, as reported by the 13th century historiographer Kirakos Gandzaketsi (dead in 1271). Writing that the famous Archimandrite Mkhitar Gosh (dead in 1213), with the support of some Armenian noblemen, built Nor Getik monastery (Goshavank), among the princes he first mentioned Haterk’s prince Vakhtang Khachentsi and his brothers, as well as Vakhtang’s wife Arzu Khatun. Gandzaketsi writes in detail about the latter, saying that she and her daughters had prepared and served the curtain of the church, which, with its beauty and illustration (also having images of the Savior and saints), surprised those who saw it. Continuing his narrative, the historiographer states that Arzu Khatun not only prepared a curtain for this church, but also for others, including Dadivank. “She prepared a curtain not only for this church, but also for Haghbat, Makaravank and Dadivank, because she was a devout woman. "

It is clear that Arzu Khatun and her daughters should have done their best to create a glorious curtain for Dadivank. We believe that this curtain made at least in 1214 was decorated the Cathedral Church in 1297 when the frescoes of St. Stepanos and St. Nicolas have been made on the right and left sides of the altar on the northern and southern walls of the church.

Since below Dadivank’s frescos will be thoroughly explored, especially in terms of iconography and art, we will make a few historical observations here. The point is that until now the opinions about the date of the making of the frescos was at the level of assumptions, based on time mentioned on the plaster of donation records on the inner walls of the church (it was mentioned before 1261 or 1312, etc.). However, now, when the date of making the fresco is known -

It is understandable that such an important initiative -

It is worth mentioning that the leaders of Dadivank, from the end of the 12th century, originated from the Haterk noble house, and we see this phenomenon in time we are interested in, when the monastery’s affairs were ruled by representatives of the Tsar branch of the Dopian prince house. Among the above-

The inscription is written inside the church, on the wall of the southern side of the altar, with red paint. It begins on behalf of the name of Hasan’s wife, Mamkan, informing that she and her son Grigor, as patrons of the monastery, have made a number of donations. Then the text goes on behalf of the prince Grigor, and another donation is being mentioned, for which his son Sargis (the clergyman) and the brothers should give a liturgy to his mother and wife. “My son, Ter Sargis and the brothers confirmed that the mass of St. Stephen’s Day should be for my mother and my wife Aspa. ” We can assume that it is not accidental for Mamkan and Aspa to choose the mass of St. Stephen’s Day, especially when we refer to the presence of St. Stephen’s fresco in the same church. Mamkan was a daughter of powerful King Kurd 1st and Khorishah (they built the church and the gavit of Yeghipatrush in Aragatsotn province, the God-

However, regardless of who has been the patron of the initiative, we can state that the frescoes of the Cathedral Church were made during the chairing of either abbot Ter Grigores, son of Vakhtang, who was remembered in 1290, or abbot Ter Hovhannes (died in 1305), who was the brother of Hasan, Mamikan’s husband.

ABOUT THE MOTIVE OF MAKING OF ST. NICHOLAS’ FRESCO

The issue of the motive for the making of Dadivank’s fresco could not have been avoided if it was similar to other famous Armenian frescos dating back to the late 13th century. We mean the selection of themes: the martyrological depiction of St. Stephen and St. Nicholas, especially the picture of the second one, which does not meet neither before nor after in the frescos of churches following the Armenian Church creed. In this regard, the opinion of art critic Lidia Durnovo is remarkable, according to whom the appearance of such a rare scene should have its own unique reasons.

We should say right away that there is no source or historic testimony directly answering this question. However, in the middle of the 13th century, a remarkable event that took place in the domain of the Dadivank bishopric allows to submit a version for the clarification of the issue. This refers to one of the excerpts of the 13th century historiographer, Archimandrite Kirakos Gandzaketsi, which he presented in a separate chapter (no 48) titled “About David the Deceiver”.

It is worth mentioning that this was a gloomy time after the Mongolian cruelty, when the people were again awakened predictions about the end of the world and every unusual thing was perceived as a heavenly sign. Kirakos Gandzaketsi begins by saying that the end of the world is near, and for this reason, the agents of the antichrist have multiplied, and then notes that in 1250, there was a hail on the sides of Khachen with fig-

We are particularly interested in the historiographer’s report that the followers praised David and called him Wonderworker. “And many followed him, and began to spread his fame and called him David the Hermit and Wonderworker. ” Continuing the story, the narrator tells about the David’s healers, the behavior of his followers with irony, indicating sectarian elements in them, but also does not conceal the fact that he enjoys a great reputation. The reason for this was that he was doing his healing free of charge, giving remission of sins, and so on. Naturally, the current situation worries church leaders. Gandzaketsi writes that soon famous monk Vanakan sends a rebuking message to David. However, as Tsar was in the area of Dadivank’s bishopric, a decisive action was being made by the head of the place arriving with a great retinue. “Bishop Grigores from Dadivank came with archimandrite Vardan and many priests because the village was in the area of their diocese. ” They try to overthrow David’s cross, which is opposed by the people. Finally, the crowd frightened by the bishop’s curse, handed David them. However, on the way back to Dadivank, they encountered the inhabitants of Garni village, who returned from the “royal court” (probably from the seat of the Mongol governor). These people, being acquainted with the happening and responding David’s request (who says he is also from Garni), ask hand David them. The bishop makes David to swear that he no longer will be involved in the same case, and released him. At the end of this story, Gandzaketsi writes that David used to say in his sermons that he was from the Arshakuni royal family and one of his sons would become the King of Armenia and the other -

Nothing more is known about David and his followers. But as we can see, after his “great hour” in Tsar, David remained in freedom and is supposed to continue spreading his ideas. It is likely that he has not forgotten soon in Tsar and in its surroundings.

What is the connection to this story with Dadivank’s fresco? Perhaps only that David was nicknamed the Wonderworker by his followers, which was also the nickname of St. Nicholas from the fresco. Although he is mentioned in the Armenian Church as Nickoghayos Hayrapet (Patriarch Nicholas), but also by his nickname Wonderworker (for example, in the 11th Century Lectionary of Catholicos Grigor Vkayaser, “Martyrology of the Patriarch Nicolas the Wonderworker”).

As it became clear from the story of Kirakos Gandzaketsi, the Bishop of Dadivank was able to stop the activity of David Tsaretsi in his diocesan territory. However, it seems that this practical step after some time has been tried in Dadivank to strengthen theoretically. Particularly, by sending a message to the people through Nicholas the Wonderworker’s fresco, that the church has its recognized saint, the real Wonderworker who was justified by Christ.

Probably it is not by chance that the martyrological episode of St. Nicholas’ getting of patriarchal power was depicted in Dadivank; on the one hand, Christ gives him the Gospel and, on the other, Virgin Mary hands him an amice. This popular iconographic version is a testimony of S. Nicholas’ undisputable reputation.

But it is surprising to see the fact of appearance of Archangel Michael in this picture, an image which with mentioned iconography (that we know hundreds of examples in Byzantine, Russian and European icon art) does not meet and is unique. The Archangel Michael, who is one of the great saints of the church, the head of the heavenly armies, is not only present on this painting, but also addresses words to Nicholas, written in the upper part of the fresco: "I am, Michael, who always keeps you and I am your collaborator since childhood” (followed by the date of the making of fresco -

Thus it is evident that the orderer or the painters of the fresco intended to emphasize in maximum the greatness of Nicholas the Wonderworker as a saint “divinely gifted” and having the “collaboration” of heavenly powers. It seems that it was done for a special purpose, as an ever-

There are many examples in the art history, when historical or social events have, in a way or other, affected the way in which the art of the given region was selected or presented. It seems that with the case of Dadivank’s fresco of St. Nicholas we deal with such a phenomenon, which is partly explained its uniqueness.

Interestingly, the other fresco on the opposite wall of that of Nicholas’, which represents the stonemasonry scene of St. Stephen Protomartyr, also has an inscription with paint of sententious characteristic. At the top of the image is Christ who extends his hand to the angels pictured on the front and says: “See the earthly nature that is suffering for me in the body.”

These words addressed to the angels, are a reminder about the martyrdom of saints (in particular, of St. Stephen) and godly gifted intercessor’s role, to which the believers who are involved in the daily rituals of the church should also be involved. At the same time, it is worth noting that these lines are literally quoted by the 12th century Armenian Catholicos Nerses Shnorhali’s verse dedicated to Stephen, “About the Protomartyr. ” This can also be regarded as a response of the Armenian reality (theological thought) in the canonical sphere of church decoration (illustration).

In summary, we can say that the double frescos on the northern and southern walls of Dadivank Cathedral were created with a specific purpose to emphasize the role of the saints and are characterized by iconographic peculiarities. The depiction of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker and the special emphasis of his power of the image and words of Archangel Michael, added on the painting, perhaps was due to the desire to neutralize the reputation of David Tsaretsi, nicknamed “Wonderworker,” who appeared in the area of Dadivank’s bishopric before the making of the fresco.

The article was published in the following book:

K. Matevosyan, A. Avetisyan, A. Zarian, Ch. Lamoureux, Dadivank Revived Miracle, “Victoria” International Charitable fondation, Yerevan, 2018, pp. 137-

References:

Մեսրոպ Մագիստրոս Տէր Մովսիսեան, Հայկական երեք մեծ վանքերի՝ Տաթևի, Հաղարծնի եւ Դադի եկեղեցիները եւ վանական շինութիւնները, Երուսաղէմ, 1938, էջ 83-

Ստ. Մնացականյան, Հայկական աշխարհիկ պատկերաքանդակը, Երևան, 1976, էջ 109-

Բ. Ուլուբաբեան, Մ. Հասրաթեան, Դադիվանք, Հայկազեան հայագիտական հանդէս, հ. Ը, Պէյրութ, 1980, էջ 7-

Դիվան հայ վիմագրության, պր. V, Արցախ, կազմեց Ս. Բարխուդարյան, Երևան, 1982, էջ 197-

Շ. Մկրտչյան, Լեռնային Ղարաբաղի պատմաճարտարապետական հուշարձանները, Երևան, 1985, էջ 38-

Թ. Մինասյան, Արցախի գրչության կենտրոնները, Երևան, 2015, էջ 33-

Ս. Այվազյան, Դադի վանքի վերականգնումը 1997-

See the French translation done from Syriac: Chronique de Michael le Syrien, Traduite en francais par J.-

Տեառն Միխայէլի պատրիարքի Ասորւոց Ժամանակագրութիւն, յԵրուսաղէմ, 1870, էջ 600։

Ժամանակագրութիւն Տեառն Միխայէլի Ասորւոց պատրիարգի, յԵրուսաղէմ 1871 (հավելված էջ 33)։

Մովսէս Կաղանկատուացի, Պատմութիւն Աղուանից, Երևան, 1982, էջ 340։

Մ. Հասրաթյան Հայկական ճարտարապետության Արցախի դպրոցը, էջ 44-

Վ. Հարությունյան, Հայկական ճարտարապետության պատմություն, Երևան, 1992, էջ 337-

Կիրակոս Գանձակեցի, Պատմություն Հայոց, աշխատասիրությամբ Կ. Մելիք Օհանջանյանի, Երևան, 1961, էջ 215-

Լ. Խաչիկյան, Աշխատություններ, հ. Գ, Աղանդավորական գաղափարախոսությունը Հայաստանում 12-

Տեառն Ներսեսի Շնորհալւոյ Բանք չափաւ, Վենետիկ, 1830, էջ 455։

© 2016-

Սույն կայքում տեղադրված նյութերը այդ թվում` բոլոր նկարները, պատկերները, տեքստային նյութերը, կարող են օգտագործվել անձնական, կրթական, ինչպես նաև տեղեկատվական նպատակներով, ArmenianArt.org կայքի անվան պարտադիր հղումով։

| Գրքեր |

| Հոդվածներ |

| Մատենագիտական |

| Քարտեզներ |

| Ճարտարապետություն |

| Քանդակագործություն |

| Որմնանկարչություն |

| Մանրանկարչություն |

| Գեղանկարչություն |

| Կիրառական արվեստ |

| Հին լուսանկարներ |

| Պատմական ակնարկ |

| Ուսումնասիրություն և վերականգնում |

| Նյութեր |

| Հայկական ձեռագիր գիրքը |

| Հնագրություն |

| Գրչության կենտրոններ |

| Վիմագրություն |

| Նյութեր |

| Մեր մասին |

| Օժանդակություն |

| Կապ |